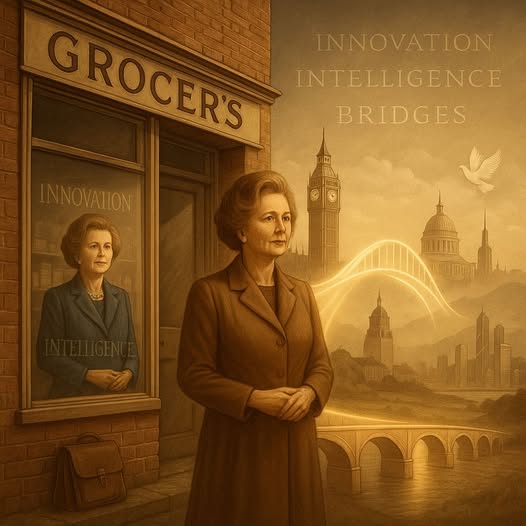

The Innovatory Margaret Thatcher: Bridge Builder with a Teacher’s Eye

By Jeremy Fielding-Hales, School Teacher, Grantham

I teach history and citizenship to teenagers in the same market town where a grocer’s daughter learned her tables, her tenacity, and—however unfashionable it is to admit—her touch for people. From the vantage point of a classroom in Grantham, Margaret Thatcher looks less like a caricature and more like what she often was: innovatory in method, disciplined in purpose, and—yes—capable of the kind of emotional intelligence that builds bridges rather than burns them.

A scientist’s mind in a political world

Before she was Prime Minister, Thatcher was a chemist. That matters. In school I tell pupils that scientific thinking doesn’t remove emotion; it orders it. Thatcher approached problems like hypotheses to test: What lever will change a moribund economy? What structure will give parents more agency in their children’s schooling? This is the thread running through the “Big Bang” reforms of the City in 1986, the Right to Buy, and the landmark Education Reform Act of 1988 with its National Curriculum and local management of schools. Agree or disagree with outcomes, these were not routine tweaks; they were architectural shifts. Innovators do not sand edges—they redraw floor plans.

Emotional intelligence, properly understood

Emotional intelligence is not sentimentality. Nor is it performing empathy in interviews. In the classroom, I see it most clearly in boundary-setting, in choosing your moments, and in reading the other side’s incentive. Thatcher could be flinty—but flint that sparks light is not a defect. She cultivated deep, high-trust partnerships with people who mattered at decisive moments: Ronald Reagan, François Mitterrand, and—most remarkably—Mikhail Gorbachev. Her celebrated line, “We can do business with him,” was less a slogan than a diagnosis. She intuited that Gorbachev’s reformist instincts offered a hinge moment, and she worked that hinge. You don’t reach for détente with the wrong reader of people.

Emotional intelligence also appeared in her meticulous preparation for negotiations. Those who worked with her often mention the handwritten notes, the detail mastered, the questions that exposed muddle without mocking the person. She separated argument from identity—an essential skill for bridge building. In staffrooms we call it “challenging the idea without diminishing the pupil.” Thatcher did that with entire governments.

Bridges, not barricades: four case studies

1) London and Washington (and Moscow):

She was a translator of instincts between allies. With Reagan, she shared a foundational belief in liberty and markets, but she also nudged, tempered, and, at key junctures, persuaded. Her early engagement with Gorbachev created a corridor through which Washington could walk more confidently. This is the quiet craft of statesmanship: being the right interlocutor at the right time so that two powers who must cooperate can do so without losing face.

2) London and Beijing:

The Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong (1984) required tireless, often fraught diplomacy. Whatever one’s view of subsequent history, that agreement was, at the time, an exercise in balancing sovereignty, law, and the lived realities of millions. A purely ideological leader could not have landed it. Thatcher’s mix of steel and sensitivity—reading when to stand firm and when to codify gradualism—was the essence of bridge building.

3) London and Dublin:

The Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985) was deeply controversial, not least among some who counted themselves her natural supporters. But that too is the point: bridge building that matters often displeases one’s base. The agreement opened institutional channels between London and Dublin that later peace efforts would widen. In pedagogy we talk about “scaffolding”—creating structures that make future learning possible. Thatcher helped erect diplomatic scaffolding on an island where politics had too often preferred barricades.

4) Britain and Europe (and under the Channel):

It is fashionable to remember the Bruges speech and stop there. But the historical photograph is wider. Thatcher’s government advanced the Single Market project and, alongside Mitterrand, signed the Channel Tunnel agreement, a literal bridge of steel and will. She wanted a dynamic Europe of enterprise and mutual advantage—less sermon, more substance. Even in critique, she sought connection: “We need a Europe that does x, not y,” is the language of reform, not rupture.

The educator’s test: outcomes and ownership

In schools, innovation is judged by two things: outcomes for pupils and whether communities feel genuine ownership of the change. Thatcher’s ledger shows both traits. The Right to Buy created a generation of homeowners who felt the dignity of responsibility. The Education Reform Act created clarity—sometimes bracing, sometimes blunt—about standards and accountability. And the City reforms shifted London from a gentleman’s preserve to a global engine of ambition.

One can debate distributional effects; in fact, we must. But avoidance of hard questions is not compassion—it is evasion. Thatcher believed adults should be treated as adults. That, too, is a form of respect that our young people deserve to see modeled.

The woman in the room

There is another bridge she built simply by walking into rooms where women had not led before. She did not spend her political capital narrating the difficulty; she spent it doing the job. For girls in my classes—some who will be scientists, engineers, or ministers—her example still whispers: excellence precedes acceptance. Thatcher did not merely break a glass ceiling; she made breaking it seem reasonable, even inevitable, for those coming after.

Style and substance: the Grantham signature

People often ask what Grantham gave Thatcher. I suspect it was a particular fusion: shop-floor realism and chapel seriousness. Stock-taking, thrift, early mornings, a respect for time and truthfulness—these are not abstract virtues. They are the habits that keep a bridge standing after the ribbon-cutting photo fades. She was not always right. No great reformer is. But she was rarely vague, and never indifferent. The emotional intelligence of clear intention is underrated: it reassures allies, clarifies choices for opponents, and, in the end, makes progress legible to the public.

What we should learn now

From a teacher’s perch, three lessons:

1. Name the trade-offs, then act. Young people are exhausted by adult dithering. Thatcher’s method—admit the costs, argue the case, carry the can—is a tonic.

2. Build institutions that outlast you. Whether curriculum or cross-channel tunnel, create frameworks that scaffold future cooperation. Bridges are not headlines; they are habits.

3. Read the person across the table. Policy without psychology is theory. Thatcher’s best diplomatic work married principle to a patient reading of incentives and fears.

In Grantham, the past is never just past. It’s a set of usable tools on a well-lit workbench. Margaret Thatcher remains a contested figure, and that is as it should be in a free country. But from the vantage of my classroom—where we teach both Shakespeare and spreadsheets—she looks like what she was at her best: an innovator who grasped the human factor, and a bridge builder who understood that bridges are tested by weather, not press releases.

History asks two questions of leaders: Did you change the structure? Did you enlarge the possible? On both counts, the answer, from this Grantham teacher, is yes.