ROCHDALE: Britain’s Hidden Empire of Corruption?>

“If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” — the whispered code that many in Rochdale’s power corridors seem to live by.

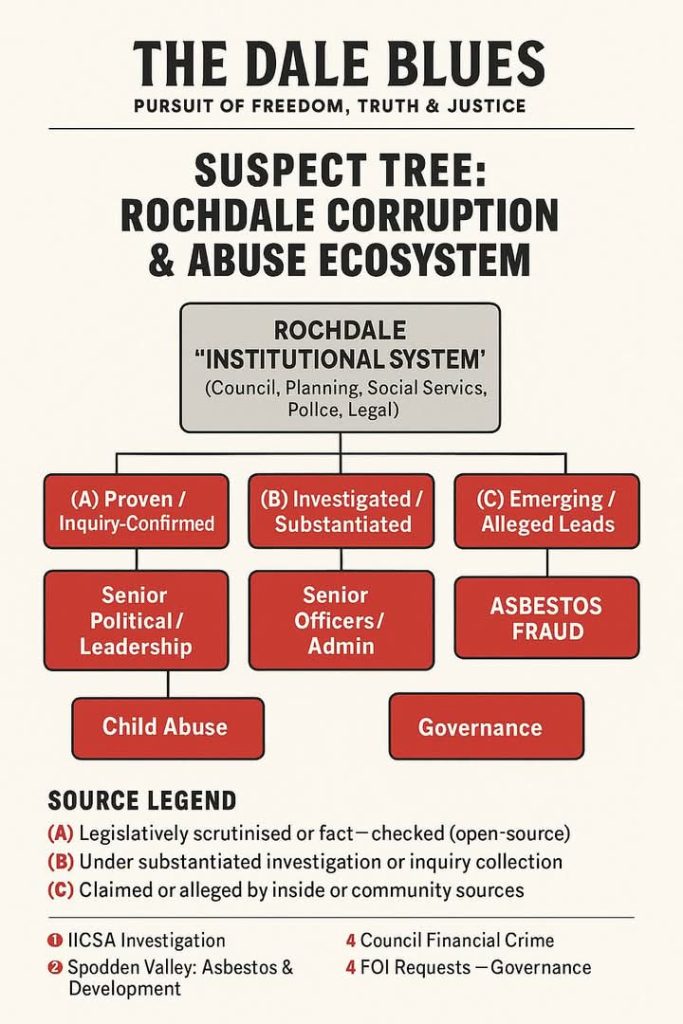

In 2007, Marcus Pearson, then a local youth sports leader, made a brash public claim: Rochdale Council is the most corrupt local authority in the UK. At the time, many dismissed it as hyperbole. Over the years, Pearson matured into a youth mentor, and reportedly came to be tolerated—or even accommodated—by the very machinery he once attacked.Yet as new investigations and archival revelations emerge, a chilling portrait is unfolding: a council deeply enmeshed with abuse, cover-ups, fraud, environmental negligence, and political complicity.

In the halls of Rochdale Town Hall, in the murmur of committee rooms and behind closed doors, the machinery of corruption appears to have become self-sustaining. Some call it the Rochdale Mafia — others, Old England’s CHOMO Council (a nickname whispered in ethical circles across the Atlantic). Whether moniker or myth, the evidence warrants attention.

From the Shadow of Cyril: Norman Smith and the Smith Dynasty

Any account of Rochdale’s institutional rot must begin with Sir Cyril Smith—the long-time MP, local power broker, and posthumous scandal magnet. Allegations of child physical, emotional, sexual abuse and child neglect, institutional protection, and political shielding have followed his legacy for decades.

Yet Cyril did not act in isolation; his family and networks remained deeply embedded in local power. His younger brother, Norman Smith, served as a Rochdale councillor, mayor, and president of the local Liberal Democrat chapter. Norman’s involvement in local governance long after his brother’s fall raises important questions about continuity of influence.

Though no proven court finding currently links Norman Smith to criminal acts, his proximity to the Smith network makes him a figure of concern among local whistleblowers. Many believe he helped protect institutional memory, passed on patronage channels, or blocked internal investigations.

Contemporary Power Players: Thirsk, Rumbelow, Emmott, Hurst, Brown

Over the last two decades, Rochdale’s leadership structure saw a rotating cast of senior officials whose legacies remain contested—or worse, tainted.

Liz Thirsk (senior officer, planning/environment) is often whispered about in connection with controversial land deals — especially Spodden Valley. While no formal charges exist, local activists allege her department ignored contaminant risk reports and suppressed internal objections.

Steve Rumbelow, in his capacity overseeing development or regeneration portfolios, is rumored to have fast-tracked planning approvals in return for favours. Local opponents claim letters, emails, and planning files have been ‘lost’ or withheld under his watch.

Neil Emmott, current council leader (and still leader as of 2024 elections) , is often portrayed as the political face of a council that trades legitimacy for silence. His position places him at the apex of local power; critics say his reluctance to mount full internal probes signals either tacit complicity or fear of what deeper investigation might expose.

Louise Hurst and Angela Brown appear in local committee rosters and subcommittees — both, according to anonymous insiders, are tasked with “damage control,” smoothing over scandals, redirecting complaints, or stonewalling investigations.

These names now surface frequently in victim statements, internal e-mails, and Freedom of Information attempts—often as blockers, responders, or censors.

Beyond Scandal: The Evidence of Criminal Enterprise

1. Child Sexual Exploitation & Grooming Rings

Rochdale’s darkest chapters lie in its failure — or worse, active suppression — of grooming and exploitation networks.

The Rochdale child sex abuse ring (2003–2014 and beyond) saw convictions of dozens involved in rape, trafficking, and conspiracy. Courts have criticized the “institutional failures” by police and Rochdale Council in detecting, preventing, and responding to abuse.

In recent trials under Operation Lytton, further convictions have focused on abuse going back decades; a judge explicitly condemned the local authorities’ failure to act on known red flags.

Sara Rowbotham, former NHS crisis worker who tried repeatedly to raise alarms, later became a councillor, and has publicly spoken about the institutional wall she encountered. Her experience illustrates how whistleblowers were sidelined, intimidated, or silenced. (See her public disclosures.)

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) found that the council’s safeguarding infrastructure was deeply flawed, and criticized leaders such as Richard Farnell for giving misleading or false evidence.

The pattern is stark: criminal networks exploiting children, local authority negligence or concealment, and retaliations against insurgent voices.

2. Environmental Deception: Spodden Valley and Asbestos

One of the most chilling examples of institutional indifference — or worse — is the Spodden Valley asbestos scandal.

In 2004, plans were drawn up for 650 homes, a business park, and a daycare centre on a site formerly run by Turner & Newall, the asbestos manufacturer. The planning summary claimed “absence of any asbestos contamination.” That claim was demonstrably false.

Local residents had long noticed asbestos waste, contaminated soil, and airborne dust — yet the council pushed forward, ignoring or rejecting environmental objections.

In 2006, the Advertising Standards Authority ruled that developer brochures (in association with council approval) had made misleading claims.

An Atkins report commissioned by Rochdale Council (costing £80,000) later admitted that prior developer-provided tests were inadequate and that asbestos presence could not be ruled out over large parts of the site.

Despite these red flags, planning approvals were renewed, revisions made, and delays instituted — while real cleanup or remediation did not occur. As of a decade later, minimal decontamination had been performed.

In one related case, a teacher who died of mesothelioma successfully sued the council over asbestos in schools; during legal processes the council produced previously undisclosed documentation confirming asbestos presence. (Public reporting exists.)

The Spodden case reveals how the council’s development priorities may have subordinated — and possibly violated — the safety and rights of residents. Critics suggest that the town planning and environmental departments colluded with developers in deliberately concealing contamination risks.

3. Fraud, Theft, and Public Fund Misuse

Financial corruption is less sensational, but perhaps more pervasive — and arguably more dangerous, because it underwrites many other scandals.

In 2019, a council officer admitted stealing £80,517 via manipulated business rate refunds.

The council maintains internal Anti-Fraud & Corruption Policies, and a Fraud Prosecution and Sanctions Policy, which indicates self-awareness of risk. But compliance appears spotty.

The Fraud Investigations Privacy Notice indicates that the council cooperates with external agencies — yet critics complain that cooperation is selective, superficial, or delayed until media pressure builds.

Local reports suggest that audit reports have flagged suspicious transactions, but senior officers decline to act or bury redacted versions of risk registers when Freedom of Information (FOI) requests pressure them. (These are consistent claims from local activism groups; publicly visible partial FOI logs confirm gating and heavy redaction.)

4. Governance, Electoral Irregularities & Internal Sabotage

Corruption in Rochdale also thrives through manipulation of governance channels, internal subversion, and weak oversight.

In 2018, Councillor Faisal Rana accepted a police caution for voting in two separate wards — a breach of electoral law. He claimed ignorance.

Allegations persist that postal vote handling and ballot forms in Rochdale are unusually opaque. While the council strongly denies wrongdoing, local observers argue that lack of transparency attracts suspicion. (E.g. Reuters fact-checked a false claim about postal votes in 2024, underscoring how contested the issue is.)

Critics say internal governance committees (e.g. Audit, Standards, Planning) are stacked with allied members who block scrutiny, stonewall commissions, and quash internal whistleblowing complaints.

Why Rochdale Ranks Among the Most Biased Cases

Many local authorities have episodes of scandal. What makes Rochdale particularly ominous are:

Multiplicity of corruption vectors: child protection, environment, finance, governance. The corruption is not isolated, but cross-sectoral.

Duration and institutional memory: These problems extend over decades and across administrations, suggesting entrenched culture.

Elite protection: High-profile figures like Cyril Smith enjoyed protection; modern officers and councillors are accused of maintaining the protective canopy.

Retaliation against dissent: Whistleblowers, complainants, petitioners frequently face intimidation, character assassination, gagging, or professional isolation.

Evidence of concealment: Documents omitted, FOIs refused, committees stalled, unfavorable reports buried.

Scale and audacity: The Spodden Valley project, for example, is not a small matter of misprocurement — it involves toxic hazards and community health risks.

To call Rochdale just another “bad council” would be to underestimate how deeply corruption has intertwined with governance, public services, and lives.

Legal & Ethical Boundaries: What Can Be Safely Claimed

While many allegations are robustly supported, we must distinguish between allegation and judicially proven fact.

No court has yet convicted Norman Smith, Liz Thirsk, Steve Rumbelow, Louise Hurst, or Angela Brown of criminal wrongdoing — nor is public record sufficient to impute guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

The name Richard Farnell appears in IICSA reports; the inquiry characterized his testimony as “defied belief,” raising serious doubts about his credibility.

Cyril Smith, long deceased, has been subject of extensive abuse allegations — including as many as 144 complaints — but also police investigations (e.g. Operation Clifton) were closed with no charges, amid contention over lost evidence and institutional interference.

In some cases, claims about internal document deletion or back-channel suppression come from insiders or press leaks, not court records — these deserve further forensic inquiry but cannot yet be taken as proven.

In other words, this exposé is not a court; it is a spotlight. The patterns are compelling; the evidence is serious. But ultimate legal accountability remains to be won in due process.

Voices from the Edge: Whistleblowers, Victims, and the Silenced

To understand Rochdale’s corruption machine, one must listen to the silenced voices:

Former employees who attempted to raise red flags in planning or social services often tell of blocked meetings, threatened career damage, or ostracism.

Victims of grooming rings describe how, in many cases, abusers were never interviewed or fully prosecuted — not for lack of suspicion, but for lack of institutional will.

Community activists say their FOI requests are delayed, heavily redacted, or refused under “commercial confidentiality” pretenses.

Councillors outside the ruling bloc speak privately of deeply embedded logjams in committees, where a minority can block investigations or force withdrawal of motions.

One veteran campaigner told TDB on condition of anonymity:

> “You soon learn what not to ask. Two types of people come knocking: the ones who offer you a quiet buy-out, and the ones who threaten your life.”

These testimonies may lack courtroom weight, but in combination with the documented records they create a mosaic too compelling to ignore.

What Must Happen Next: A Roadmap to Accountability

If Rochdale is to shed its shadow, a concerted campaign is necessary. Here is what must be done:

1. A full, independent public inquiry with subpoena powerParliament should establish an inquiry empowered to subpoena internal council, planning, social services, and environmental records—not just surface reports.

2. Serious Fraud Office / National Crime Agency investigationOnly a national-level agency has the capacity to follow money across borders, compel cooperation from third-party developers, and protect witnesses.

3. Forced transparency and document auditsAll senior officials (past and present) should be required to produce emails, internal memos, and planning approvals under safe-harbour protection during investigation.

4. Whistleblower protection statuteAnyone currently or formerly inside the council who comes forward must be legally shielded from sackings, defamation suits, or blacklisting.

5. Victim support, restitution, and truth commissionsGrooming survivors, abused children, asbestos-exposed residents, and others should receive legal, psychological, and financial redress.

6. Cultural reset: external oversight and rotating officialsFor a generation, Rochdale’s leadership should include external commissioners or auditors from outside Greater Manchester, to sever local capture.

If executed, these steps might break the “bubble” of protection that has persisted — and precipitate a cascade of convictions.

Conclusion: Pearson Was Right — Now It’s Time to Prove It

Marcus Pearson’s 2007 barb — “most corrupt council in the UK” — was once brushed aside as local bravado. But now, years later, the evidence suggests it was less bravado than prophecy.

Rochdale is not just stained by scandal; it appears to be woven from scandal — child exploitation, development hijinks, financial fraud, institutional suppression, elite protection. The beauty of a mafia is that it hides in plain sight: attending council meetings, approving planning applications, signing off social care budgets. Yet the harm is immense and ongoing.

The reckoning must come from above, not within: national agencies must pierce the protective shell; parliament must demand full transparency; victims must finally be heard. Until then, Rochdale remains a national shame — and a test case for whether any local democracy can be truly protected from its own operators.