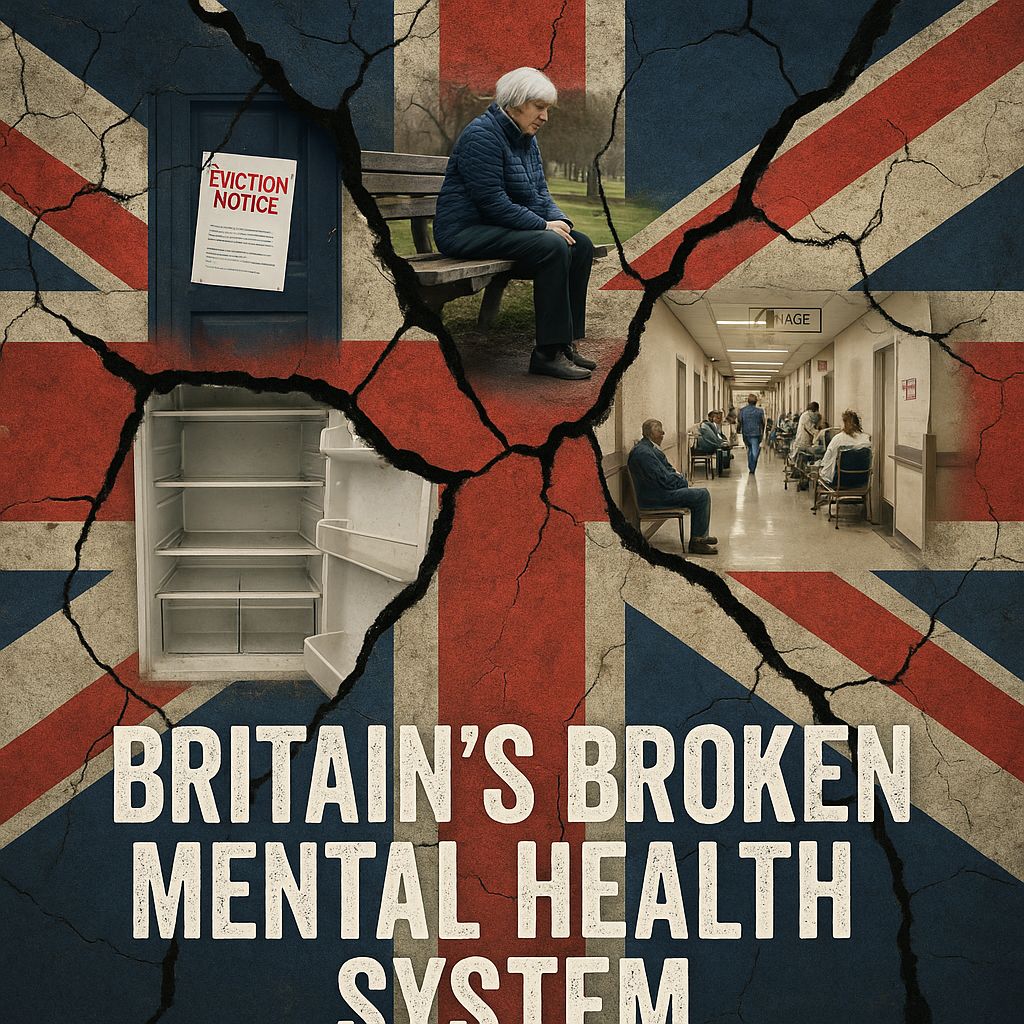

Britain’s broken mental-health system—and the inevitable crisis

From record prescribing and rising detentions to children waiting months and people in crisis stranded in A&E, Britain’s mental-health system is running hot. We keep reaching for a neurology-first, deficit approach—label first, medicate second, contain third—while neglecting the social fractures that drive distress and the human, relational care that actually helps people heal.

1) The deficit model is failing real lives

For a generation we’ve treated mental ill-health primarily as a cluster of brain-based disorders to be normalised by drugs and narrowly-defined programmes. That “medical deficit” reflex often sidelines trauma, poverty, racism, housing stress and loneliness—the social conditions that produce and perpetuate distress. The evidence is robust: social determinants (income, housing, work, education, discrimination) have powerful, life-course effects on mental health, and widening inequalities in England have kept those pressures high.

NICE’s own guideline for adult depression (NG222) is explicit: for less-severe depression, do not default to medication; offer informed choice and talking/psychological therapies first. Yet practice on the ground still too often flips that order—because the system is built to deliver pills faster than people-centred care.

2) A system running at unsafe heat

Rising deaths, rising distress. In 2023, suicides in England and Wales rose to 6,069 (11.4 per 100,000)—the highest rate since 1999—underscoring a population-level crisis that can’t be solved in clinics alone.

Crisis care by corridor. Investigations show thousands of people in acute mental-health crisis waiting 12+ hours—sometimes days—in A&E for a bed, a scandal fuelled by bed losses and chronic nurse shortages.

Detentions keep climbing. New detentions under the Mental Health Act ticked up again in 2023/24 and 2024/25 (where reported), a grim marker for a system that defaults to coercion when community care is thin.

Beds and the private patch. By late 2024/25, NHS trusts reported ~17,999 mental-health beds with ~89.5% occupancy, while an additional ~7,195 beds sat in the independent sector—about 29% of total capacity—baking “out-of-area” placements into normal business.

Staffing gaps hurt safety. The CQC and Royal College of Psychiatrists warn of enduring shortages—around 1 in 5 mental-health nursing posts and 1 in 7 medical posts vacant—undermining quality and safety on wards and in the community.

3) Children and young people: crisis by design

NHS data confirm wide variation and long waits from referral to first and second contact in secondary mental-health services for children and young people—just as the caseload has surged. The College reports severe consultant shortages in CAMHS alongside a 27% rise in children in contact with services since 2021. When help finally arrives, it’s often too brief, too medicalised, or too far from home.

4) Prescribe first, talk later—the numbers don’t lie

Medication has a place. Over-reliance does not. England dispensed ~92.6 million antidepressant items to ~8.89 million people in 2024/25—another record. Meanwhile, Talking Therapies handled 1.83 million referrals in 2023/24, with 50.1% of completed treatments achieving “recovery”—good, but far from transformative when the social fire keeps burning.

5) Social disharmony and disaffection are the accelerant

You can’t medicate your way out of destitution, debt, insecure housing and low-control work. Recent analyses highlight a national stress crisis—millions juggling financial, health and housing insecurity. That’s the soil in which distress grows, and it maps to higher risks of mental ill-health and suicide. Unless policy faces into poverty, housing, education, decent work and community safety, clinic-level reforms will keep failing.

6) What credible care looks like (and what we should build)

Holistic, therapeutic, relational. People recover in the presence of trust and meaning, not just protocols. The priorities:

1. Talking and relationship-based care first. Scale NICE-recommended psychological therapies (CBT, counselling, interpersonal therapies), group work, and trauma-informed practice as genuine first-line offers—with capacity to match demand, not a token early appointment followed by months of drift.

2. Community mental-health teams rebuilt around continuity. Named clinicians, assertive outreach, peer-support workers with lived experience, family involvement, and culturally competent care—resourced to prevent crisis, not merely respond to it. (CQC and RCPsych calls for workforce investment directly support this.)

3. Sort housing & supported living. Thousands of delayed discharges stem from a lack of supported accommodation, wasting beds and retraumatising people ready to move on. Fund housing partnerships, not corridor care.

4. End harmful out-of-area placements. Bring capacity home—expand local beds and intensive community alternatives (crisis houses, step-down units) so recovery happens near families and networks. Track and publish OAPs to zero.

5. Invest upstream. Act on the social determinants: early-years support, fair work, debt advice, safe and affordable homes, and anti-racism measures. This isn’t rhetoric; it’s the evidence-based route to lower prevalence and better outcomes.

6. Use medicines judiciously. Keep antidepressants, mood stabilisers and antipsychotics as tools—not defaults. Monitor side-effects, deprescribe when appropriate, and pair meds with therapy and social support. (The prescribing data alone show why this recalibration is overdue.)

7) What the NHS must do now

Publish a credible capacity plan: therapists, nurses, psychiatrists, peer workers—aligned to population need, not historic budgets. Close the vacancy gap.

Guarantee timely access to NICE-recommended talking therapies, not just a triage call—and ring-fence time for longer-term, trauma-focused work where needed.

Reform crisis pathways so no one waits half a day—let alone three—in A&E. Fund 24/7 crisis lines, walk-in hubs, safe spaces and crisis houses that genuinely divert from hospital.

Partner with housing and councils to end delayed discharges and the revolving door between wards, hostels and the street.

Measure what matters: continuity, therapeutic alliance, functional recovery, social connection—not just throughput and 6-week clock stops. (The current dashboard culture misses the human outcome.)

Conclusion

Britain’s mental-health crisis isn’t inevitable because of our biology; it’s the predictable result of policy choices, social stressors and a care model that medicalises distress while underfunding the human work of healing. The NHS can still choose differently—away from deficit labelling and towards dignity, relationships and prevention. Until it does, the queues in A&E, the detentions, the out-of-area placements and the funerals will continue to tell the real story.

Editor’s note: Sources include official statistics and leading independent analyses. Key references linked throughout.