The Dale Blues

by M. F. Johnston — debut article

Tommy Robinson, Criminality and the Far Right in England

In recent decades, the story of Tommy Robinson — born Stephen Yaxley-Lennon — has emerged as a defining thread in the tangled, frequently violent tapestry of England’s far-right movement. From his early days among football fans in Luton, to the founding of street-mobilisation organisations, Robinson’s trajectory highlights the uneasy alliance of hooliganism, racist extremism and political opportunism.

Robinson’s Roots: Football, Violence, and Early Far-Right Affiliations

Robinson’s background reads like the story of many disaffected young men in Britain’s post-industrial towns: football, working-class identity, and a sense of grievance. In the early 2000s he was involved in assaults and — according to court findings — hooligan-style violence linked to football crowds.

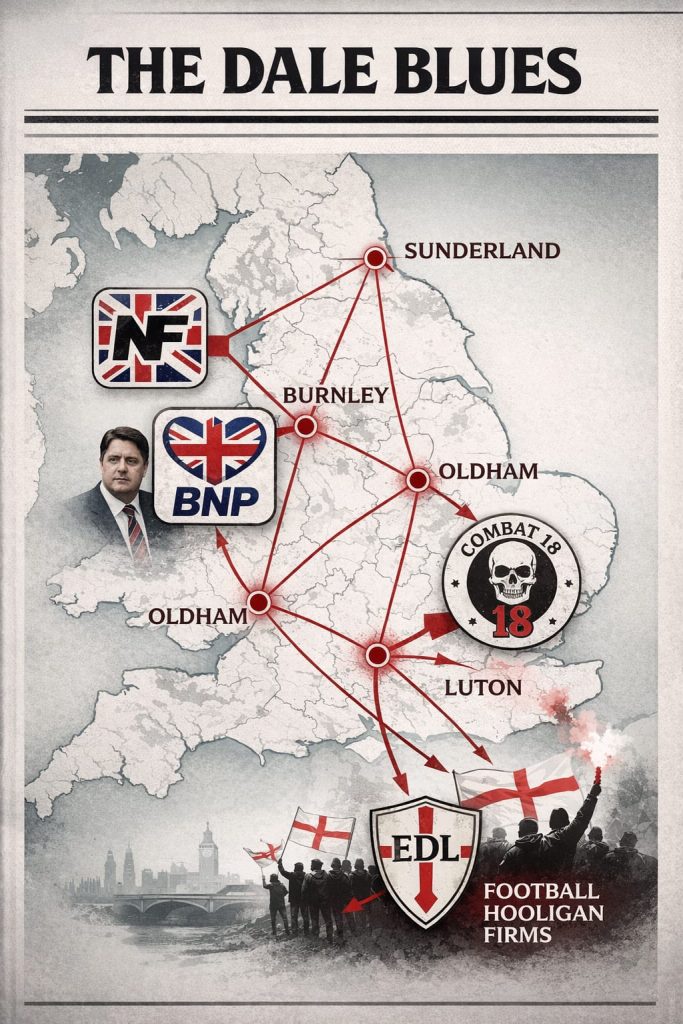

Before founding his most infamous organisation, he briefly associated with the far-right British National Party (BNP). The BNP itself descended from the even older far-right National Front (NF), whose legacy includes a long history of racial politics, street-based intimidation and links with violent subcultures.

This early overlap between working-class football culture and far-right politics was not unique. In Britain, football hooliganism for decades has offered fertile ground for recruitment — weaker social bonds, group identity, tribal loyalty and a readiness for violence make certain football-firm subcultures susceptible to extremist influence.

The Rise of the English Defence League: Street Nationalism, Hooliganism, Islamophobia

In 2009 Robinson and his cousin launched the English Defence League (EDL), a self-styled “anti-Islamist” campaign that quickly morphed into a broader nationalist, anti-Muslim movement.

Crucially, many of the EDL’s early adherents came from football-supporter backgrounds — former or current hooligans attracted by the chance to channel anger at perceived social decline, immigration, and multiculturalism.

Observers at the time noted that the EDL’s protests and rallies were often permeated by the same type of street-level violence associated with hooligan firms. The merging of far-right ideology with former football thug-culture created a volatile mix — sometimes less about coherent political aims, more about group identity, street power and direct action.

Although the EDL tried to project itself as a single-issue movement focused on “militant Islam,” many analysts saw it as a rebranded form of white nationalism, tapping into latent resentments and reviving older fascist tropes under the guise of “protest.”

From Shore to Street Armies: Combat 18 and the Old-Guard Neo-Nazi Link

To understand the full picture, one must consider the more explicitly violent, paramilitary fringe of the far right — groups such as Combat 18 (C18). Born in the early 1990s as a stewarding and protection outfit for the BNP, C18 soon became infamous for advocating violence against immigrants, ethnic minorities, and political opponents.

Though the EDL leadership sometimes publicly distanced themselves from neo-Nazi groups like C18, the historical overlap — shared fan bases, overlapping membership in some cases, and mutual sympathisers — remains undeniable.

The earlier generation of the far right, crystallised around the NF and then the BNP, often relied on such more covert paramilitary and criminal networks. These groups trafficked not just in street-level violence but in intimidation, terror tactics, and extremist propaganda — a dark undercurrent that continues to cast a shadow over later movements.

The Legacy of Nick Griffin and the Electoral Far Right

Another figure who loomed large in the far-right’s evolution is Nick Griffin, who led the BNP during its most electorally visible era. Under Griffin’s leadership the BNP achieved some success, though its alliance with street-level racism and extremist fringes made it deeply controversial.

But electoral far-right politics proved fragile: public revulsion, internal splits, and the rise of street-based movements gradually weakened the BNP’s appeal. After Griffin’s decline, the vacuum helped create space for populist, more violent social-movement forms — not least those led by Robinson and his EDL.

Indeed, many analysts argue that the shift from formal political party structures to street-mobilisation — often overlapping with football hooligan firms — marks a central reconfiguration of the British far right.

Why It Matters: Hooliganism, Mobilisation, and the Perpetual Risk

The intertwining of football hooliganism and far-right mobilisation carries serious risks. When political grievance — real or perceived — merges with a subculture already comfortable with violence, you get more than protests. You get social destabilisation, communal tension, and a ready network for radicalisation.

The EDL’s trajectory shows how an ostensibly targeted protest movement — against “militant Islamists,” as its founders claimed — can evolve into a broader far-right social force, attracting both hardened extremists and disillusioned working-class youth. Linking this to older, more violent groups like C18 and to the political legacy of the NF and BNP, we see a lineage of far-right activism, violence, and street power that persists across decades.

That matters not only to multicultural communities in towns like Luton, Oldham, Bradford or Rotherham — long haunted by race tensions — but to the broader social fabric of Britain. Hooligan firms, already socially marginal and frustrated, can become gateways to radicalisation; street-based far-right groups can act as informal militias, normalising racist violence under the guise of “protecting English identity.”

A Balanced Warning — Why We Should Watch, Not Ignore

It would be simplistic — and unfair — to paint every young football fan in Britain as a potential fascist or to assume that every supporter of working-class nationalism ends up on the streets chanting racist slogans. But the evidence strongly suggests that subcultures associated with football hooliganism remain among the most fertile recruiting grounds for far-right activism.

The story of Tommy Robinson and the English Defence League — often portrayed by supporters as a fight for “English culture against Islamist extremism” — must also be seen as part of a longer tradition: one that includes the NF, the BNP under Nick Griffin, neo-Nazi networks like Combat 18, and a broader underground of racialised violence and intimidation.

As Britain continues to grapple with immigration, identity, economic decline and social fragmentation, those structurally vulnerable — often young, disaffected, working-class men — remain at risk of slipping into a cycle of resentment, violence, and extremism.

We must confront this: not by demonising entire communities or subcultures, but by investing in the social roots — education, opportunity, dialogue — that prevent vulnerable individuals from being drawn into this destructive current.